Published in Windlesora 31 (2015)

© WLHG

War is indeed a fearful thing and the more I see of it, the more dreadful it appear

Prince George, 2nd Duke of Cambridge after Sebastopol

In this plethora of anniversaries which fall in 2015, the Battle of Agincourt (Azincourt as it is known in France) does not probably rank as high in the public perception as Magna Carta, two hundred years earlier and Waterloo, four hundred years later. Yet the Battle of Agincourt was of no less importance in its decisive overwhelming by the English Army led by Henry V over the considerably greater forces fielded by the French, than Wellington’s crushing defeat of the Emperor Napoleon in 1815. Indeed, Winston Churchill, writing in 1955, opined that the Battle of Agincourt represented the shattering ‘of French power by a feat of arms which, however it may be tested, must be held unsurpassed’ and, moreover, that ‘Agincourt ranks as the most heroic of all the land battles that England has ever fought’.

In 1415 the respective sovereigns of England and France were Henry V and Charles VI. In that year Henry was twenty-eight years of age and Charles, fifty-three, but it was only Henry who rode at the head of his army. Charles, on the other hand, had for many years suffered severe bouts of insanity which had earned him the soubriquet of ‘Charles the Mad’ by which he is known to history, and he took no part in the battle. It is ironic that when he was younger it was said of him:

He had all the fortunate dispositions of youth; he was a Skilled archer and javelin thrower, loved war, was a good horseman and showed great impatience whenever the enemies provoked him or attacked him

The overall command was with Charles d’Albret, Constable of France.

The first clash of arms of the campaign took place at the Siege of Harfleur in September 1414, and it was a bloody prelude of what was to come. The victory was wrought by Giles, Henry’s Master Gunner and his ten cannon, each capable of hurling projectiles of two hundred pounds. This initial success was immortalised by William Shakespeare:

Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more

Or close the wall up with our English dead

What the Bard failed to make clear was that the French defeat at Harfleur took much longer than expected due mainly to the tenacity of one of the town’s leaders, Raoul de Gaucourt, and that the English forces would be numerically diminished by injuries, disease and death. Despite strong counsel that having gained Harfleur, and in the light of his depleted forces, it behoved Henry in the interest of prudence to sail back to England. Henry, however, was as determined as his foes had been at Harfleur. He decided to adhere to his original plan, to march his army the one hundred and twenty miles to Calais in the hope and expectation of meeting and defeating a French army in a pitched battle on the way, and then to re-embark his army homewards from the English-held port of Calais. However, a serious miscalculation on the part of the English stemmed from their intention to march north to the Somme and to cross the river a little to the east where it debouched into the Baie de Somme, at a place then known as Blanchetaque.

Unfortunately, the French were already grouped in strength on the north bank and since the ford was only sufficiently wide for twenty men abreast, the odds in favour of the enemy were immense. Henry, accordingly, was obliged to head east to find an alternative crossing.

His army, depleted further by the ravages of dysentery, found crossing after crossing held by the French providing similar disincentives as before to hazarding an attack. At last, beyond Amiens, an unguarded ford was found and the tired and dispirited army were able to head north again towards Calais. But the vast French army was waiting.

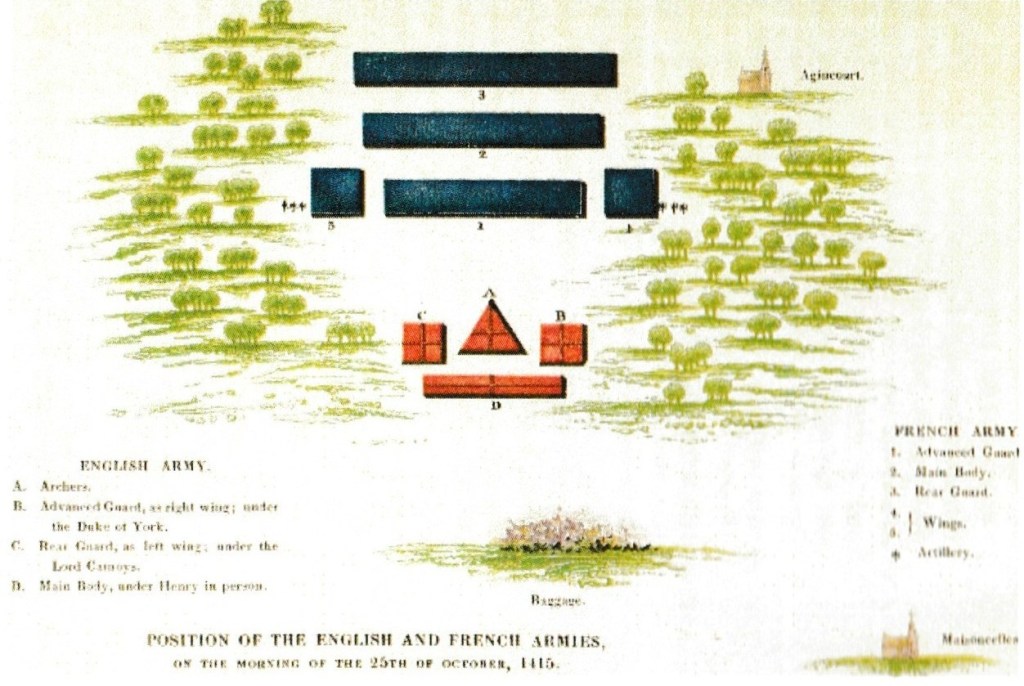

On 24 October, the English army camped near the small village of Maisoncelles. Some two and half miles away to the north-west stood another village, Azincourt, a little to the east of which lay the French army. The battlefield consisted of a vast field, some two miles long and a mile wide. At about halfway along its length were situated two woods, one on each side impinging upon the field and reducing the gap between the two woods to little more than half a mile. It was just short of this ‘neck’ that Henry was to establish his front line.

On the fateful day, 25th October, Henry rose at dawn and heard Mass. It was the feast day of St Crispin and St Crispinian, two brothers martyred in Soisson, on the orders of Emperor Maximillian circa 288 AD. Only too aware of the numerical inferiority of his army against that of the French, and of its sixteen-day sickness-plagued march from Hlarfleur, the King made one last effort to reach a settlement with his opponents. He offered to surrender Harfleur in exchange for an uncontested road to Calais. The heralds galloped back and forth but d’Albret demanded in addition that Henry renounce the Crown of France. This Henry refused to do. His response was Churchillian in its indomitable defiance and ensured that battle would now be joined.

Many writers, some knowledgeable and some less so, have argued over the centuries since the struggle took place as to the numbers on each side. The generally accepted consensus, however, is that the six thousand-strong army of England faced a host totalling some thirty thousand Frenchmen; a ratio of five to one. The French army was drawn up across the field where it began to narrow on account of the encroaching woods on either side and was faced by Henry’s army within the ‘neck’ thus created. The former comprised three great phalanxes, each containing eight or nine thousand soldiers. These formations were known as ‘battles’. Henry’s troops, in considerably smaller numbers, faced them within the ‘neck’ between the two woods.

After the armies had eyed each other warily for several hours, Henry, riding a small grey horse and wearing a bright heraldic surcoat, with a jewelled crown upon his head, gave the order at around 11.00 am.

In the name of Almighty God and of St George, Avaunt Banner in the best time of the year and St George this day be thine helped.

The English army advanced to within three hundred yards of the enemy.

Henry’s troops were almost entirely composed of men at arms and archers, the latter outnumbering the former by about six to one. It was the archers who were to prove the decisive factor in England’s victory. Positioned on either flank, the bowmen of England numbered about five thousand well-trained marksmen. The six-foot Welsh longbows with their Sheffield steel arrowheads, flighted with goose feathers, or sometimes with feathers from their Captains’ peacocks, had proved their worth at Crecy sixty| years before.

The English had been ordered to cut six-foot pointed stakes, which they now pushed deep into the ground before them forming a bristling obstacle to the enemy advance. As for the archers, it has been calculated that a good archer could shoot at least twelve arrows in a minute. With five thousand archers in the field, a rain of sixty thousand arrows a minute fell upon the foe. Infuriated, the first French attack by mounted men at arms faltered, horses and men alike falling to those terrible, feathered shafts and many lying impaled on the sharp stakes. France’s problem was that it had nothing to match the English bowmen.

It is worth recalling at this point a not irrelevant 1975 case in England’s Court of Appeal – that of New Windsor Corporation vs Mellor, in which a solitary but intrepid Windsor citizen, Miss Doris Mellor, backed by the Windsor and Eton Society, succeeded in claiming Bachelor’s Acre as a Town Green within the meaning of the Common’s Registration Act of 1965. As appears from Lord Denning’s judgement, evidence was led to the effect that:

In medieval times it was the meadow where young men practised with their bows and arrows. A pair of butts was set up there. They shot at the targets.

Those bows were the long bows of Crecy and Agincourt, and their possessors, the Yeomen of England, as musically remembered in Sir Edward German’s ‘Merrie England’. It is not beyond belief that Windsor men fought in these battles.

There now entered the battle England’s greatest ally- ‘General Mud’. As another French army four hundred years later suffered at Waterloo, so did their ancestors suffer at Agincourt. On both occasions, torrential rain had fallen during the preceding night. When therefore the first two battles of the French army, horses and men encased in armour, moved forward to the attack into the narrowness of the ‘neck’ they floundered in their heavy armour in a quagmire. As men and horses in the first ranks were brought down by the never-ceasing rain of arrows, so those behind were impeded by the fallen in front of them, for once down, whether killed or not, it was nigh impossible to rise again, The archers for their part exchanged their bows for swords, poleaxes, and clubs and fell vigorously upon their adversaries.

Henry, himself, was in the thick of the struggle distinguishing himself in particular by rescuing his brother, Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, who had been wounded in the melee.

There on that blood-soaked field perished the flower of France, Among, their dead was counted d’ Albret, the Constable, the Dukes of Alencon, Brabant, and Bar, the Archbishop of Sens, ninety Counts, over fifteen hundred knights, and four or five thousand men at arms. The Dukes of Orleans and Bourbon and the Marshal of France were captured. The English dead, who included the King’s cousin the Duke of York, have been estimated at a mere two hundred.

The rear phalanx of the French army turned and fled the field.

A terrible episode that has been used to besmirch Henry’s conduct on the battlefield was the killing of a large number of prisoners who had been taken behind the English lines, however many of these captives had broken free and were attacking Henry’s baggage train. He could not afford to leave these so-called prisoners, with few men to guard them, loose in the rear of his army and objective writers have conceded that his action was justifiable. Most certainly, immense savagery on both sides characterised this battle, but again this was a recognised feature of those times. Ever afterwards the French categorised their defeat as ‘La Malheureuse’ (‘the unfortunate day’).

| KG No. | Name and Title | Year |

|---|---|---|

| 76 | Edward of Norwich, later 2nd Duke of York | 1387 |

| 91 | Sir Simon Felbrigge | 1398 |

| 93 | Henry Prince of Wales, later King Henry V | 1399 |

| 96 | Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester | 1400 |

| 103 | Sir Thomas Erpingham | 1401 |

| 114 | Sir Gilbert Talbot of Irchingfield | 1408 |

| 115 | Sir Henry, later 3rd Baron Fitzhugh | 1409 |

| 116 | Sir Robert Umphraville | 1409 |

| 117 | Sir John de Cornwall, later Ist Baron Fanhope | 1409 |

| 121 | Thomas Montacute, 4th Earl of Salisbury | 1414 |

| 122 | Thomas de Camoys, Ist Baron Camoys | 1415 |

Henry V and Charles VI died within a few months of each other in 1422. Before the open tomb of Charles at St Denis, the Duke of Berry pronounced the ritual words:

Lord have mercy on the soul of the most high and excellent Prince Charles, King of France, the sixth of that name, our natural and sovereign Lord

and then, after a minute’s silence, he continued,

Long Live King Henry VI, by the Grace of God, King of France and of England.

Agincourt is immortalised by Shakespeare:

And Crispin Crispian shall never go by

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remembered;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers

Five hundred and twenty five years later another Few would likewise be immortalised by Winston Churchill.

John Handcock

Sources:

Lives of the Kings and Queens of France, Duc de Castries

History of the English Speaking Peoples Vol. 1, Winston S Churchill

Azincourt, Bernard Cornwell

Henry V, Peter Earle

Encyclopaedia Britannica

History Today Companion to British History, Gardiner & Wemborn

A Concise History of Warfare, Lord Montgomery of Alamein

Saints and Symbols, Olwen Reed